ATHENS/QAMISHLI, Syria: Since 2022, senior Syrian and Turkish officials have met regularly in Moscow under Russian mediation. But these meetings have failed to thaw icy relations.

But things are different now, as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has announced his intention to restore formal relations with Syrian President Bashar Assad.

He said earlier this month that he could invite Assad to Turkiye “at any time”, to which the Syrian leader responded that any meeting would depend on “the content”.

Ankara and Damascus severed diplomatic ties in 2011 following the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. Relations have remained hostile since then, with Turkmenistan in particular continuing to support armed groups opposing the Assad regime.

Since the civil war broke out in 2011, Turkiye has supported armed Syrian forces fighting against President Bashar Assad's regime. (AFP)

So what is the motivation for the change of direction now? And what are the expected outcomes of the normalization of Turkey-Syria relations?

Syrian writer and political researcher Shoresh Darwish believes Erdogan is pushing for normalization for two reasons. “The first is preparation for the possible arrival of a new US administration led by Donald Trump, which could mean a return to the policy of withdrawal from Syria,” he told Arab News.

“Therefore, Erdogan will have to cooperate with Assad and Russia.”

This photo released by the Syrian Arab News Agency shows President Bashar Assad (right) meeting with then Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Aleppo. (SANA/AFP)

The second reason, Darwish said, was that after the war in Ukraine, Turkmenistan had tilted toward the United States, and Erdogan wanted to move closer to Russia, an ally of the Syrian regime. Indeed, as a NATO member, the conflict has complicated Turkmenistan’s generally balanced approach to relations with Washington and Moscow.

“Cooperation between Ankara and Moscow on the Ukraine issue is difficult,” Darwish said. “As a result of the West's considerable interference in this issue, their cooperation in Syria represents a meeting place where Erdogan seeks to emphasize his friendship with Putin and Moscow's interests in the Middle East.”

Turkey-backed opposition forces in northwestern Syria view the reconciliation between Ankara and Damascus as a betrayal.

Protesters in the opposition-held Idlib and Aleppo countryside wave Syrian revolution flags and hold placards reading: “If you want to get closer to Assad, congratulations. History has cursed you.” (Ali Ali photo)

At one of several demonstrations in Idlib since early July, protesters held signs reading in Arabic: “If you want to get closer to Assad, congratulations. History has cursed you.”

Abdulkarim Omar, a political activist from Idlib, told Arab News: “Western Syria, Idlib, rural Aleppo and all the areas where there are opposition forces, we reject this action completely because it serves only the interests of the Syrian regime.

“The Syrian people rose up 13 years ago and launched a revolution demanding freedom, dignity and the establishment of a civil democratic state for all Syrians. This can only be achieved by overthrowing the tyrannical Syrian regime represented by Bashar Assad. They are still obsessed with these principles and slogans and cannot give them up.”

People living in areas controlled by the Kurdish-led, US-backed Autonomous Administrative Region of Northeastern Syria (AANES), which occupies most of the Syrian territory east of the Euphrates River, are also wary of the consequences of normalization.

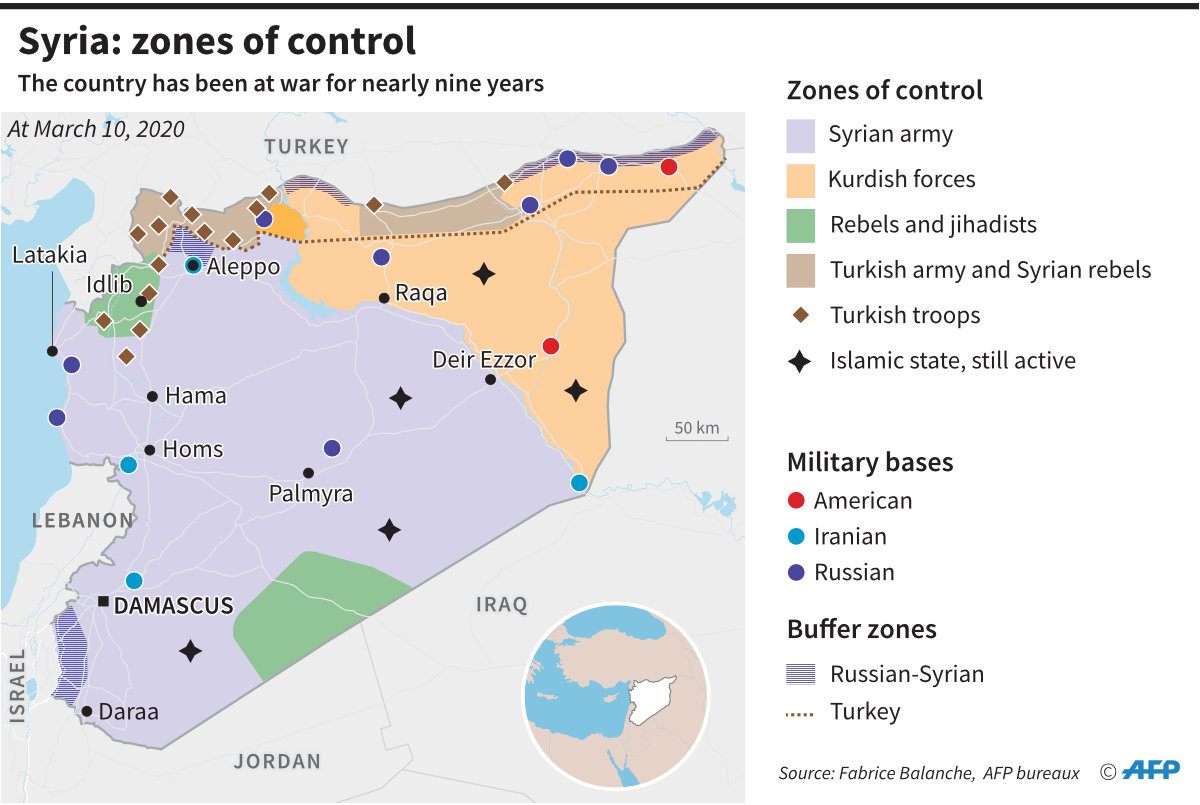

A map of Syria showing areas controlled by various actors in late 2020. Some towns that were under the control of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces at the time have been taken over by Turkish forces. (AFP/File)

“There are concerns among the people that reconciliation could be a prelude to punishment for the political choices of the Syrian Kurds,” Omar said.

During the invasion of Syria from 2016 to 2019, Turkmenistan took control of several cities, many of which were previously controlled by AANES.

Turkey's invasion and continued presence in Syrian territory in 2018 and 2019 was aimed at creating a “safe zone” between Turkey and the Syrian Democratic Forces (AANES).

Members of the Syrian Kurdish Asayish security forces stand guard as mourners march during the funeral of two Kurdish women killed in a Turkish drone strike in Hasakah, northeastern Syria, June 21, 2023. (AFP)

Turkey views the SDF as the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), a group that has been at odds with the Turkish government since the 1980s.

“Of course, the Syrian Kurds know that Erdogan will participate in any deal he wants to make with Assad,” Darwish said. “This issue makes the Syrian Kurds nervous. They see Turkiy as willing to do anything to harm them and their experience of autonomy.”

Darwish said Syrian Kurds would accept reconciliation under three conditions: First, they want to see Turkiye withdraw its forces from Afrin and Ras al-Ain; second, Turkish airstrikes on the AANES area must stop; and third, the Assad regime must guarantee “Syrian Kurds the enjoyment of their national, cultural and administrative rights.”

In this photo taken on January 27, 2018, a Turkish military convoy passes through the Onkupinar border crossing as troops enter Syria during military operations in the Kurdish-held Syrian town of Afrin. (AFP/File)

But how likely is a reconciliation between Ankara and Damascus? Not at all, according to conflict analyst and UNHRC representative Thoreau Redcrow. “I think the chances of a reconciliation between Erdogan and Assad are very low,” he told Arab News.

“Historically, Turkiye’s idea of ‘normalization’ with Syria is a unilateral influence policy that serves Ankara’s interests. In this agreement, Turkiye continues to occupy Hatay (Li and Iskenderun), which it took from Syria in 1938, and makes military demands for sovereignty, as in the 1998 Adana Accords, but gives nothing in return.”

Assad has made it clear in public statements that any meeting between him and Erdogan will only take place on the condition that Turkey withdraws from Syrian territory. Redcrow believes Turkey has no intention of leaving.

“It is hard to see how Damascus is interested in being manipulated for photo ops,” he said. “The Syrian government is much more proud of being one of Turkey’s ‘neo-Ottoman vilayets’ than other regional actors.”

Erdogan may be trying to capitalize on the normalization trend among Arab states that began in earnest last year with Syria’s return to the Arab League. But European countries and the United States remain divided.

Syrian female soldiers parade in an opposition-controlled area in northern Syria. (Photo courtesy of Ali Ali)

“Germany, France, Italy and especially Britain are more focused on how Turkey can control the gateway to Europe and act as a ‘continental bulwark’ for refugees from the Middle East and West Asia, while the US is more focused on denying Russia and Iran full access again across Syria for strategic reasons, such as access to the Mediterranean and the ‘Shiite land bridge’ from Tehran to Beirut,” Redcrow said.

“The status quo is far more beneficial to Washington than any reconciliation, because it would put at risk the areas in northeastern Syria where American troops are deployed alongside their most trusted military partners against Daesh in the SDF. Turkey would therefore not be given any kind of license to put American interests at risk.”

The U.S. House of Representatives passed the Assad Regime Anti-Normalization Act of 2023 in February, which prohibits normalization with Assad. The bill’s author, Rep. Joe Wilson, expressed disappointment in Erdogan’s call for normalization in a July 12 post on social media platform X, likening it to “normalizing with death itself.”

Although reconciliation may seem unlikely at this point, even rumors of normalization are met with fear and dread by the estimated 3.18 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

“People are very scared,” Amal Hayat, a Syrian mother of five from the southeastern city of Turkiye, told Arab News. “Since the rumors (of reconciliation) started going around, many people don't even leave their homes. If they get beaten by their bosses at work, they don't say anything because they are afraid of being expelled.”

A Syrian woman is seen at a refugee camp near the Syrian-Turkish border. (Photo by Ali Ali)

According to Human Rights Watch, Turkish authorities have deported more than 57,000 Syrians in 2023.

“Forced return will have a huge impact on us,” Hayat said. “For example, if a woman returns to Syria with her family, her husband could be arrested by the regime. Or what if a man is deported to Syria and his wife and children remain in Turkiye? It's difficult. Our children can study here. They have stability and security.”

Fears of expulsion have been heightened by a wave of violence against Syrian refugees that has swept southern Turkey in recent weeks. On June 30, residents of the central Turkish province of Kayseri attacked Syrians and their property.

Anti-Syrian sentiment among the Turkish public is partly economic: Turkish people see low-paid or even unpaid Syrians as a threat to their job prospects.

“The Turks are very happy that we are coming back,” Hayat said. “It's not too early for them. We are all under a high level of stress. We just pray that (Assad and Erdogan) do not reconcile.”